Class Oral Storymaking

Andrew Wright is an author, illustrator, teacher trainer and story teller. He has published with Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press and Pearson. As a teacher trainer and story teller he has worked in 55 countries. Email: andrew@ili.hu,

www.andrewarticlesandstories.wordpress.com

What are stories?

Stories are descriptions of events in which protagonists struggle to achieve something. They may be factual or fictional descriptions.

Why make stories?

Motivation: we all need stories every day.

Re-cycling language: what better way is there?

Experiencing language: creating something new with what we have

and caring about doing a good job.

Communicating: trying to make the story clear and engaging

Springboard activities: activities naturally arising from making stories.

Storymaking skills: given we are all storytellers to a greater or lesser extent then it follows that improving our skills in story making is a good idea!

Which language and age levels?

We all need stories. Story making is very satisfying if you have just started learning a language and very challenging if you are an advanced learner!

The question and answer technique for making a class story

Estimate about 40 minutes to make an oral class story.

This amazingly simple technique is just one way of helping students to make stories. I learned the technique from Word in Action and I have used it in over 40 countries and at all levels of English.

In the lesson plan given below I have tried to show how the technique can be done at low and at higher levels.

Summary

Making stories together as a class, lead by your questions, is a very useful way of demonstrating to all the students how to create a strong storyline and how to create characterful people, places, objects and situations. I suggest you do this oral storymaking on a fairly frequent basis.

The technique is driven by your questions. It is best for you not to have an idea what the answers should be. The work of the students is to create their story and not to find out what you have in mind!

|

Essentially, you ask questions, they answer, you collect and re-tell their story. They re-tell their story later. The basic questions are: Who do you want in your story? Where are they (at the beginning of the story)? When is it? What are they doing? And then? |

Elementary language level

Keep to the simple questions above only ask supplementary questions if you think they can answer them.

Above elementary level

Start with the very simple questions but follow on with questions you think they can answer and which help to enrich the story and to drive it on.

Example of developing questions

Who do you want in your story?

How old is she?

What’s her name?

What does she look like?

Brown? What kind of brown?

Tell me about her character?

Etc. through to advanced learners:

Would you describe her as an extrovert or an introvert?

Procedure

1 Ask the class: Who is in the story? Is it a man, woman, boy, girl or an animal?

2 Ask the class: What is his/her/its name/age?

Continue according to the proficiency level of your students. Your further questioning is your opportunity to drive their creativity to greater particularisation.

Students in the class call out answers. You collect all the answers. They call them out in the present tense but you then keep re-telling the story so far in the past tense. Do NOT change things to make them more sensible according to your ideas!!!

Example re-telling their first responses:

You: There was a girl. She was 14 years old. She had dark brown hair and she was very tall. She was two metres tall.

2 Ask the class: Where is he/she/it at the beginning of the story?

Is he/she/it in a city or a town, or a village or in the country, etc.

3 Ask the class: When does the story begin?

Months of the year, weeks, days, seasons, times in the day.

4 Ask the class: What the weather is like?

Is it raining, snowing, windy, stormy, sunshining, etc.

5 Ask the class: what is he/she/doing?

Hiding, sleeping, eating, cooking, reading, etc.

Crying, laughing, shouting, etc.

Ask questions to invite them or push them to say what happens next. Only use your suggestions for what happens next as a very last resort and if you do then give at least three possibilities. If you give them a choice they will feel that the story remains theirs.

A key tip for this technique: include everything you hear!

Built on years of using this technique! Several answers might be called out. You must not select one of these answers but include ALL of them in the growing story. This is vital for three reasons:

- It is not your job to select the best one but their job to make the story.

- Sometimes you might get two answers one from each of two cliques of student. To stop all rivalry which will destroy the technique say, ‘Whatever I hear will be in the story!’

- Sometimes you might have two or more ages offered. You can respond in this way: I heard that she is 14, 25 and 120. How can she be 14, 25 and 120? Somebody might give you an answer. If they can’t you can say, ‘Well, people were not sure how old she was. Some people thought she was 14, other people thought she was 25 and others thought she was 120.’This immediately begins to make the story unique!

And if you can’t remember all these additions when you re-tell the story then the class can help you! Brilliant! They have to listen carefully in order to make sure you tell and re-tell the story correctly!

Another key tip for this technique: you re-tell the story not them!

Of course, we all know that the students must be as active as possible! But in this technique you must not lose the momentum of the story making by getting them to re-tell it! Your driving momentum will keep all the class listening even if many do not actually call out any answers. That is already a massive achievement!

Lots of mini tips for doing it well!

- Ask the questions but try not to have in your mind a good answer…be open to any ideas even those which seem silly at the time.

- Don’t add ideas to make it better from your point of view.

- Don’t show special enthusiasm for one suggestion and none for another because this suggests that you have a hidden storyline which you want them to confirm instead of letting them feel it is THEIR story.

- Don’t ask closed questions: Is it a boy? Give lots of alternatives so it is a genuine choice. Is it a boy, a girl, a man, a woman or an animal, etc.?

- Don’t correct mistakes but in your re-telling give the correct version.

- Every so often re-tell the whole story. If you have been using questioning to drive the class towards detailed characterisation then you will not be able to remember it all when you do the re-telling. If you are working with a creative class above elementary level then I suggest you have two ‘secretaries’ to write down key phrases denoting special details suggested.

- Don’t ask the students to re-tell the story while making it…this is worthy but damaging to the dramatic pace necessary for making the story come alive.

- Remember: you are the story collector not a guide to higher qualities (at least, not on the surface!)

- From beginners be happy with single word suggestions and from more advanced students expect phrases or occasionally full sentences.

- The questions given above are not sacrosanct in choice nor in sequence! Begin with the weather or with a woman crying or a box. See below.

Some variations on Question Story Making

Pictures, fortune telling cards, word cards, texts, sound recordings, objects

You can have any of these things to stimulate the next part of the story. In our classrooms the walls are covered with pictures and with the question and answer technique the entire story can be illustrated by the pictures on the wall.

You might write on the board, ‘walking’. Then you might ask, ‘Who is walking?’ ‘Where… When…How…Why….?

You might write on the board, ‘nobody likes the cat’. Then ask questions about the cat and what the situation might be, might have been, etc.

Class plus group making

You can establish who the key protagonist(s) is or are with the whole class and then each group creates a story based on where, when, what. The whole collection of stories when published can be attributed to the same character.

Group making

You can ask the four basic questions but ask each group to discuss the answers and decide on the story. One could be the secretary for his or her group.

Pairs rather than the whole class

Ask questions but the students work in groups or pairs to create the answers.

You ask the questions and the students working with their partner decide on their answers together in order to create two people. Tell them that the two characters must be very different

Very important is to establish a ‘desire and difficulty’ for each person they create. They may relate the ‘desire and difficulty’ for each created person or choose quite different ones. The desire and difficulty struggle and resolution is the seed of the story.

A few really good springboard activities

Dramatising the story

Estimate at least 60 to 80 minutes if you include dramatizing each section.

When I worked with Word in Action using this technique we kept stopping and dramatizing the story so far or section by section of it. Students volunteered to be protagonists but also to be trees or chairs or rooms. For example 16 students hold hands and make a room. One student is a door which opens and closes. The chair might be a kneeling student and another standing as a back to the chair. You might re-tell the story as they act but you might also ask them to do the dialogues in the story.

Making a book

Estimate at least 40 to 80 minutes on this work extra to the story making.

But you can be sure that many of the students will do a lot of the work in their own time because the book is not for you…they will exhibit their book and they want it to look as good as they can make it. Nothing to do with marks!

The examples I have chosen range from very young children who made a story but couldn’t write through to very competent teenagers.

Different contributions from different levels:

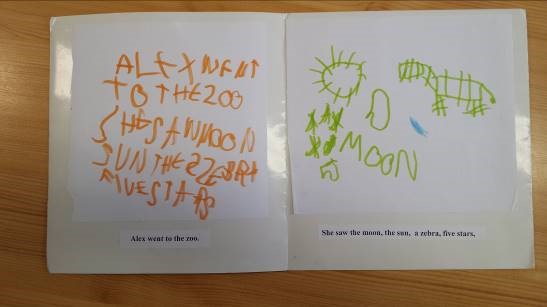

- The children beginners and young. They make a story with me. I write up their story and put it into a book. The children add the illustrations.

- Ditto 1 above but the children add some of their own texts.

- Having made the story as a class, groups write and illustrate the whole book by themselves.

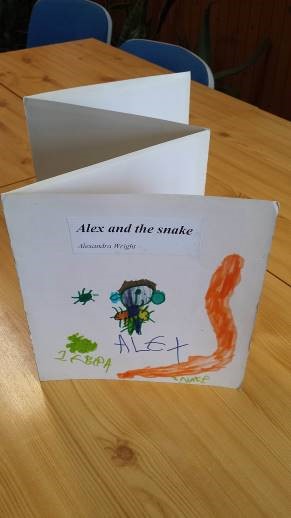

Alex who has autism wrote this 8 page zigzag book when she was about seven. You can see that we worked on it together. Sometimes I typed her sentences and sometimes she wrote her own sentences.

With children who can make a story with me orally but cannot write I write the story for them…type it onto the different pages in the book…then photocopy the book and give it to them to illustrate. In this case with Alex it is a mixture! English is Alex’s second language.

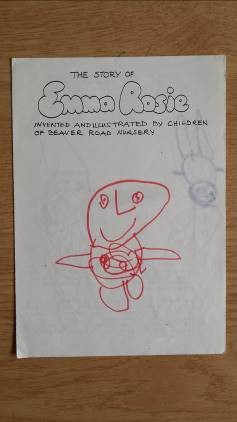

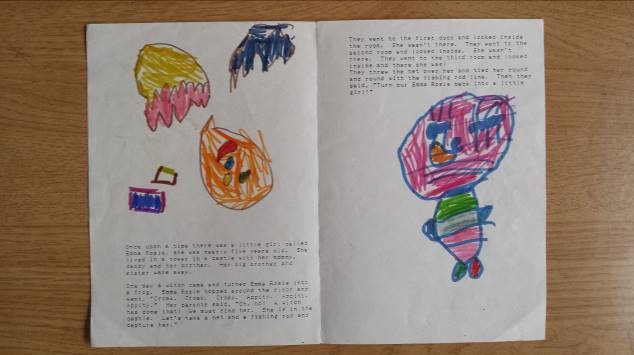

A class of children aged four made this 4 page story about Emma Rosie in their mother tongue. I went home, typed up their story as you see below, photocopied enough for copies for each member of the class and explained to them that it was their story and their book. They illustrated it…matching their illustration with what they believed to be the text on that page.

This book by Tim was done entirely by him for me. He was seven and a native speaker of English. Of course it was easier for him because he was writing in his mother tongue. BUT the point is that he chose to do this in his own time and chose to give it to me! What a treasure!

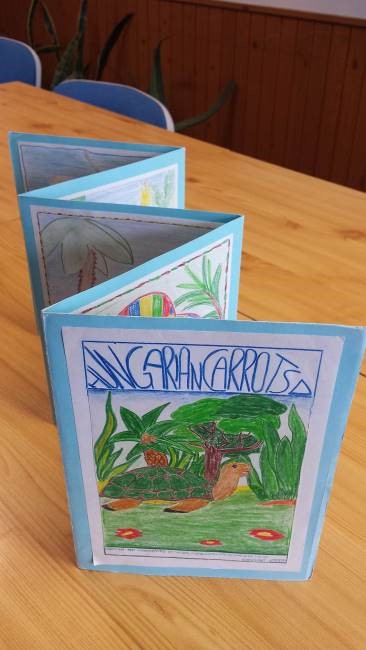

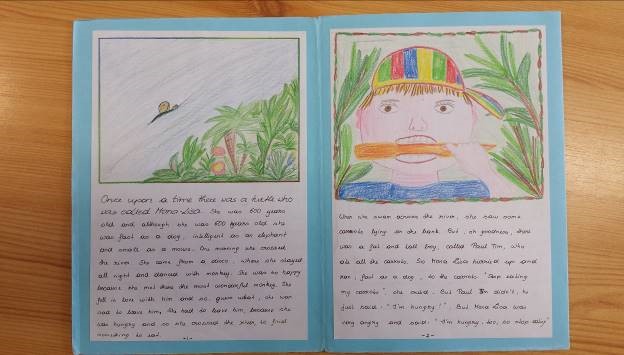

This is a ten page zigzag book. Each white sheet is A5. It was made by a group of Austrian teenagers following a story making. Each teenager wrote and illustrated two or three pages. Most of the work was done in their private time and they did it because they loved doing it.

One mother in the town told me that her son was setting his alarm clock early so he could go to school and work with his group on their book before school started!

Because they work on separate sheets of A5, it is easy for the whole group to be working at the same time and easy for you to check the language before it is pasted in to the book…if that is what you want to do.

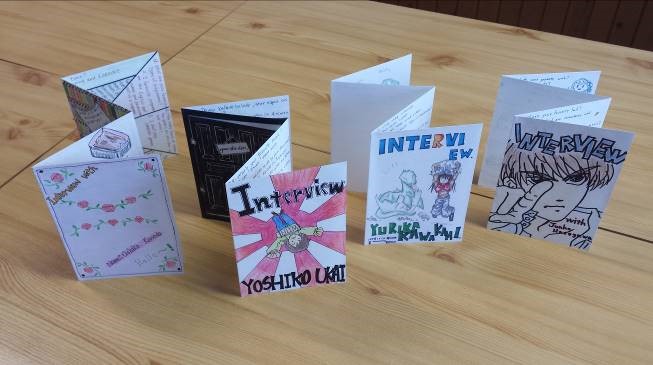

I worked in Chubu Gakuin University in Japan with the students. These were some of the zigzag books they made. Once more they went ‘far beyond the call of duty’ and spent a lot of private time on them. Book making is relevant to all ages and abilities.

When the story is finished you might very reasonably say, ‘Gosh! That’s a super story! We can’t just lose it! We must make it into a book. Lets make different books in groups. Get together in 3’s or 4’s or 5’s. Here is the zigzag book you are going to have. Its got a cover and 7 pages (can be more). You can work on it together…and decide if you each do two pages or whether one person writes and the others draw.’

‘To help you lets divide the story into seven parts and then you will know what to write and draw on each page.’

The class then brainstorm what they think the seven parts might be. You act as their secretary and write on the board for them to copy. If they are elementary you might even write the sentences for them to copy. If they are higher level you can write key words to help them with the story and the language they will need.

Books are wonderful because you can exhibit them in the school AND you can go to the school director, show him or her the books and then ask for money to attend APPI conferences.

Publish the stories for others through: books, posters, websites, plays, videos, audio recordings.

A true false re-telling

In the next English lesson tell them what a great story they made and begin to re-tell it but incorrectly. They will call out to correct you.

It was a great story about a boy…

A girl!

Oh, sorry yes a girl. She was fifteen years…

Fourteen!

Etc.

Homework

Ask the students to write up their version of the class story for homework. Tell them they are allowed to change the story to make it better.

|

Biggest tip of all! Be joyful if your cup is half full that means it is not half empty! Enjoy it! We only live once! Share your joy with them! Hop about and shout Yippee!...or however you express such things. |

Further reading

David Heathfield (2014) Storytelling with our Students. London. Delta

Andrew Wright (Sec Ed 2004) Storytelling with Children Oxford University Press. This book contains 32 stories and lesson plans and 92 different activities you can do with any story. Children and teenagers.

Andrew Wright (1997) Creating Stories with Children. Oxford University Press. Lots of ways of helping children to make stories and story books. Children and teenagers.

Andrew Wright and David A. Hill. (2008) Writing Stories. Helbling Languages. More suitable for teenagers

Please check the Methodology and Language for Kindergarten course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Class Oral Storymaking

Andrew Wright, HungaryReaching At-Risk Students in a 5th Grade EFL Classroom

Stephanie Ptak, South Korea