Teacher and Student Images for Forced Online Education

Heather M. Austin is a versatile and engaging EFL Instructor who has an MA in Applied Linguistics and over a decade of experience in the TESOL field in Turkey and Japan. In addition to teaching preparatory English, EAP, and ESP, she has been actively involved in materials development, curriculum design, educational technology integration, committee work, and conducting research. Her professional and scholarly interests include discourse analysis, Second Language Acquisition Theory, English for specific purposes, extensive reading, and educational technology. She takes pride in being a competent, well-rounded educator with a strong belief in cultural exchange and professional development.

Mary Jane M. Özkurkudis is a lecturer and the Head of the Curriculum and Material Development Unit in the School of Foreign Languages, Preparatory Program at Izmir University of Economics. She an MA in Curriculum and Instruction. She also has a TESOL Advanced Practitioner Certificate. She believes in continuous education, gives importance to professional development, and takes every opportunity for self-improvement. She has written five articles, two of which were published in a journal scanned in the Web of Science (WoS) database.

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic forced classes to move online in a matter of weeks, leaving teachers and learners confused as they adjusted to an unfamiliar way of conducting lessons. Metaphors generated by individuals when describing their experiences are a personal representation of their lived reality and can provide insight into the unconscious views they hold. Therefore, teacher and student metaphors about forced online education at a university in Turkey were collected and analyzed. Implications are discussed, including the benefit of teacher reflection on their own and their students’ beliefs, using metaphors to identify shortcomings and guide institutions offering online education.

Introduction

Many fundamental aspects of life have changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic: social interactions became limited with lockdowns and social distancing; hospitals overflowed, making medical assistance inadequate or difficult to access for a time; and workers struggled to stay afloat as a result of being furloughed, losing their jobs outright, or having to declare bankruptcy as their small businesses went under. Neither was education spared from the far-reaching consequences of the global pandemic, and classes were forced to continue online all over the world as of March 2020. The transition was abrupt, and it pushed many teachers and students to their limits as they tried to adapt to an unfamiliar way of conducting lessons. With COVID-19 continuing to spread and a vaccination still in the works, the Fall 2020 semester at a private university in Turkey was planned to be fully implemented online using the Blackboard Learning Management System© (LMS) for synchronous and asynchronous lessons. Teachers and students were familiar with this LMS, but the situation was still far-from-ideal for many. Or was it? What have teachers’ and students’ experiences of forced online education during the COVID-19 pandemic been like? These questions regarding this extremely unique situation sparked the objective to study their attitudes, as reflected in the metaphors and similes reported in this paper.

One conclusion drawn is that there is value in teachers analyzing their own and their learners’ attitudes toward online education, especially those who had never taught online before. This leads to a reflection on online teaching practices which can improve the quality of their online lessons. Another conclusion drawn is that the evaluation of teachers’ and students’ images can more clearly – likely due to their emotive power and the way in which metaphors are able to extend to all sensory modalities (Ortony, 1975, p. 51) – inform institutions of shortcomings that need to be addressed within the online education medium.

The rushed pace of transitioning online and the limitations posed by the COVID-19 pandemic certainly restricted an optimal roll-out of online courses, but all things considered, the data presented in this study has great potential to be utilized both in teacher development and in institutional endeavors to improve these courses, especially those that will continue to offer online programs after the pandemic is more under control. This paper taps into previous research that demonstrates the value of the methodology used, metaphor analysis; it gives evidence to reinforce the notion that when teachers conduct such analyses, it can have positive effects on their own attitudes and teaching practices; and it provides examples of how the vivid images of metaphors have great power in suggesting improvements that need to be made for a more quality online program.

Literature Review

Metaphor analysis, which is a type of discourse analysis, has become “a popular avenue for understanding social phenomena” (Redden, 2017) as metaphoric language can be seen as both “an economic form of meaning-making” as well as “a way of making sense of experience for oneself and others,” (McGrath, 2006, p. 173). This type of analysis sprung up from the seminal work of Lakoff and Johnson (1980), Metaphors We Live By, in which they explore the role of metaphor in human cognition. While they explain the essence of metaphor as being the understanding or experiencing of one thing in terms of another, metaphor is also a fundamental system by which people conceptualize their world and behavior (Gibbs, 2008). Ortony (1975, p. 50-51) highlights that the metaphor a person uses provides a vivid image of that person’s emotional reality and perceptual experience. For example, someone describing marriage as a ‘battle’ probably has a rather different lived experience of marriage than someone who describes it as a ‘dance’ or a ‘team sport.’ The differing connotations between these metaphors are quite clear, and they may suggest not only additional metaphors (the husband and wife as ‘opponents’ versus ‘dancers’ or ‘teammates’), but also different possibilities for action (‘fighting’ versus ‘collaboration’) (Tracy, 2019). Metaphor analysis is a powerful tool that can shed light on unconscious attitudes and assumptions that both “characterize and drive action,” (Bullough, 1991, p. 51, as cited in Zheng and Song, 2010) – with the concept of metaphors influencing action, including teaching practices, also supported by the likes of Lakoff and Johnson (1980); Thornbury (1991); Moser (2000); McGrath (2006); Zheng and Song(2010); Lawley and Tompkins (2014); Redden (2017); and Tracy (2019), among others. Thus, “…the way we think, what we experience, and what we do every day is very much a matter of metaphor,” (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, p. 4). This is particularly important because, as Ortony (1975) points out in his inexpressibility thesis, a metaphor has the ability to capture inexpressible information that is seemingly impossible to articulate in any other way without losing the potency of the intended message. As such, metaphors give people the capacity to express themselves more thoroughly by relying on the inherent nature of metaphor to “circumvent the problem of specifying one by one each of the often unnamable and innumerable characteristics” of what they are trying to describe (Ortony, ibid.: 53). This is done by transferring what is called a set of ‘distinctive characteristics’ that are appropriate and reasonable. For example, in the sentence ‘The earthquake destroyed the building as if it were a house of cards,’ we must first examine what we might be assumed to know about a house of cards. This likely includes such characteristics as being flimsy, vulnerable to movement and wind and, therefore, can easily collapse. Other characteristics of a house of cards may include its construction, the way it was slowly and carefully built, each card supporting the other with just the right balance, usually with no adhesives or other external connecting methods to keep them in place. However, this latter description is not what (should) reasonably comes to mind when reading the simile, that is, assuming the comprehender has enough background knowledge on what house of cards is. The former description is thus characterized as ‘appropriate distinctive characteristics’ because what the simile (it should be noted that a simile is, in fact, a metaphor) is doing is, effectively, saying “take all of the features you know peculiar to a house of cards which could reasonably be applied to a building in an earthquake and attach the entire set of them to the building.” If this doesn’t happen, the comprehender either failed to understand the metaphor or attributed an inappropriate set of characteristics to the topic and misunderstands (Ortony, 1975). Nevertheless, if done correctly, the power of metaphor to function as a “bridge” for people to gain a deeper cognitive understanding of a potentially new, abstract, or not well-delineated concept is an extremely economic and impressive feature of language and human cognition (Zheng and Song, 2010).

The basis of metaphor analysis, which is a method of discourse analysis, is that “by examining the metaphors that human beings use in describing their experiences and beliefs, people can begin to uncover meanings beneath those [metaphors] directly and consciously…” to understand how they conceptualize their world (Zheng and Song, 2010, p. 42). Essentially, metaphor analysis has the potential to make the implicit assumptions that underpin our perspectives more explicitly accessible.

Research questions

What are the teachers’ and students’ perceptions of online education?

a. What are the teachers’ attitudes toward online education?

-

-

- How does the teachers’ attitude toward online education impact their teaching?

-

b. What are the students’ attitudes toward online education?

ii. How does the students’ attitude toward online education impact their learning?

c. Are there any similarities or differences between the teachers’ and students’ perceptions of online education?

Methodology

Redden (2017) notes that “asking people to relate their experiences to metaphors can prompt critical thinking and evaluation, and make for nice comparisons for researchers to analyze,” (p. 3). Therefore, metaphor analysis, as an alternative, experiential qualitative research method, was well-suited for this study in its aim to identify teachers’ and learners’ attitudes toward online education, and issues in teaching and learning online during the COVID-19 pandemic. Quantitative and qualitative data was collected via two online surveys (one for teachers and one for students), a statistical analysis of recorded answers and demographic information from the survey, and follow-up semi-structured interviews. This was then followed by data-driven coding of survey responses and an analysis of the findings.

Participants

Taking a forced metaphor approach to metaphor analysis (Tracy 2019), over 50 instructors and nearly 250 students within the School of Foreign Languages, made up of the Preparatory English Program, the Undergraduate English Program, and the Second Foreign Languages Program, at a private university in Turkey.

Data collection tools

Participants were surveyed to complete the prompt ‘Online education is like…’ and provide a brief explanation in the form of a ‘because’ sentence. In addition to the metaphor prompt and ‘because’ sentence, demographic information was also collected. These surveys were administered online at the end of the Fall 2020 semester, which was the first planned fully online semester at this university due to the continuing spread of COVID-19.

For the teacher survey, the data requested included: (1) gender, (2) how many years of teaching experience they had, and (2) whether or not they had taught online before the COVID-19 pandemic. Item number two was broken down into grouped years, such as 1-3, 4-6, 7-10, 11-13, 14-16, 17-20, and 20+. For the student survey, the following data was also collected: (1) gender, (2) their year in school, and (3) whether or not they felt they could easily access online courses (good internet connection, reliable computer at home, necessary software, etc.). For item number 2, though 1st- 4th year students were naturally included, only the two highest levels of the Preparatory English Program students (C and D Levels) were surveyed due to the language limitations of lower-level learners of English in being able to produce metaphors and express themselves adequately in English. Therefore, the language level of all students who participated is assumed to have been at least B1 or higher according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR).

Classification of Data

Inspired by McGrath (2006), who conducted a similar metaphor analysis on teacher and student views of coursebooks, the researchers followed similar steps for the classification of data for both survey responses. Two tables containing a selection of teachers’ and students’ responses and further explanations will follow.

- All [HK1] images were listed

- Images that appeared semantically related were put into the same group

- Overarching categories were determined for each group with images that expressed mixed feelings appearing neutral; images that did not clearly lend themselves to the devised categories were set to the side

- A closer examination of the responses, including ‘because’ sentences, prompted the refinement of certain categories

- A final review of the categories led to the notion of a positive-negative continuum

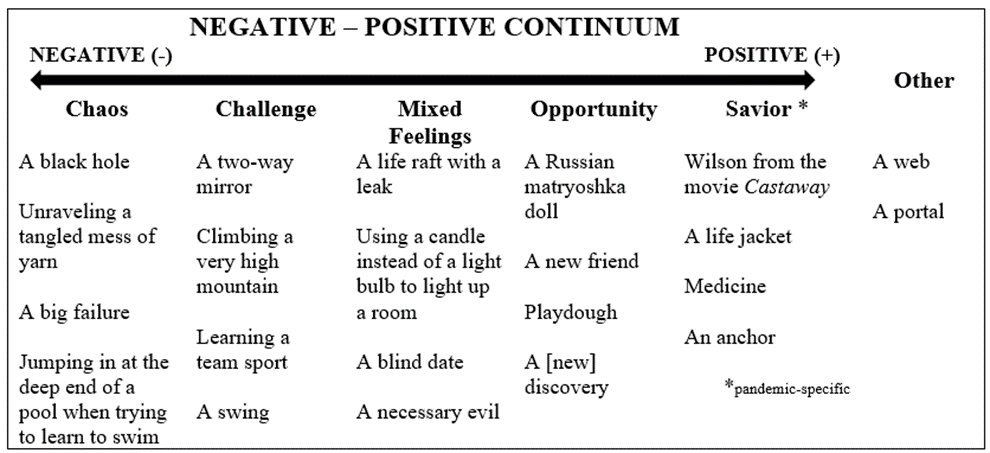

Table 1. Teachers’ Images

In Table 1, teachers’ images were categorized into five main themes: Chaos, Challenge, Mixed Feelings, Opportunity, and Savior. Creating the descriptors of each category was a helpful guide when placing each image in a category, particularly for the more negative labels of Chaos and Challenge. These can be read in full in Appendix A. The Mixed Feelings category was particularly interesting because, as McGrath (2006, p. 175) points out, they demonstrate that despite a metaphor prompt being a seemingly simple task to complete, the pro-and-con images generated are actually a testament to the level of thought such an activity can stimulate.

Some of the images were relatively simple to place, such as ‘Online education as a black hole’ or ‘a life jacket,’ but for others, the ‘because’ sentences played a key role in the overall categorization process. When comprehending a metaphor, there is of course the possibility that certain people may be more attuned to characteristics other than the speaker’s intended ones due to the unique experiences and knowledge they have of the topic (one person may fixate on the speed of a rollercoaster while another may focus more on its track of ups and downs). However, the ‘because’ sentence gave the participant the opportunity to clarify the features of the comparison that they wanted to highlight in their own experience. For example, the image of a rollercoaster came up three separate times from three separate teachers, and each ‘because’ sentence revealed a different intended meaning as illustrated in these examples:

|

Online education is like a rollercoaster because… |

|

|

Challenge: |

‘when you feel like you got the hang of it, it keeps surprising you and all you want to do is to scream and hope you won't crash.’ |

|

Mixed Feelings: |

‘it is fast, fun, yet unpredictable with many ups and downs.’ |

|

Opportunity: |

‘you are up and down and you never know when you are up and down.’ (This was later clarified in a follow-up interview to mean that the experience of online teaching was thrilling and was seen as an opportunity to reflect and learn) |

The ‘because’ sentence was also an important factor in helping the researchers identify the correct ‘appropriate distinctive characteristics’ that were intended by the participants. For example, one student said, ‘Online education is like a song.’ At first glance, the connotation and experiences we personally have of a song are likely aligned with the concept of music, which is, for most people, a positive thing filled with emotion, memories, and sing-a-longs. However, the student’s ‘because’ sentence clarified the inaccuracy of this assumption: ‘because you can let it play in the background :-D’ (smiley face in original). This shows the irony of the student’s intended meaning because, while online education would ideally make students actively listen, pay attention, and participate to commit input to memory, this student instead focused on the more passive characteristics of songs, or rather, online education’s ability to be passive as it does not require the use of cameras or microphones (at least at the university in this study) and does not demand the student’s attention as the student likely multitasks doing other things during the lesson – a stark contrast from the initial characteristics that came to mind. Therefore, the ‘because’ sentences helped guide the researchers in interpreting and categorizing many of the participants’ metaphors.

The “Other” category was used for images that were not clearly positive or negative despite referring to the ‘because’ sentence. The ideas themselves were clear, but as follow-up interviews were voluntary and these particular teachers did not agree to a follow-up interview, it was not possible for the researchers to determine whether these ideas were intended to be interpreted as positive or negative.

|

‘Online education is like a web because it connects students, teachers, ideas, machines and all other elements together.’ |

|

‘Online education is like a portal because it allows you to reach students through a kind of window. How clearly students can see through that window to access and be involved in the learning involved depends on how well you maintain the transparency of it.’

|

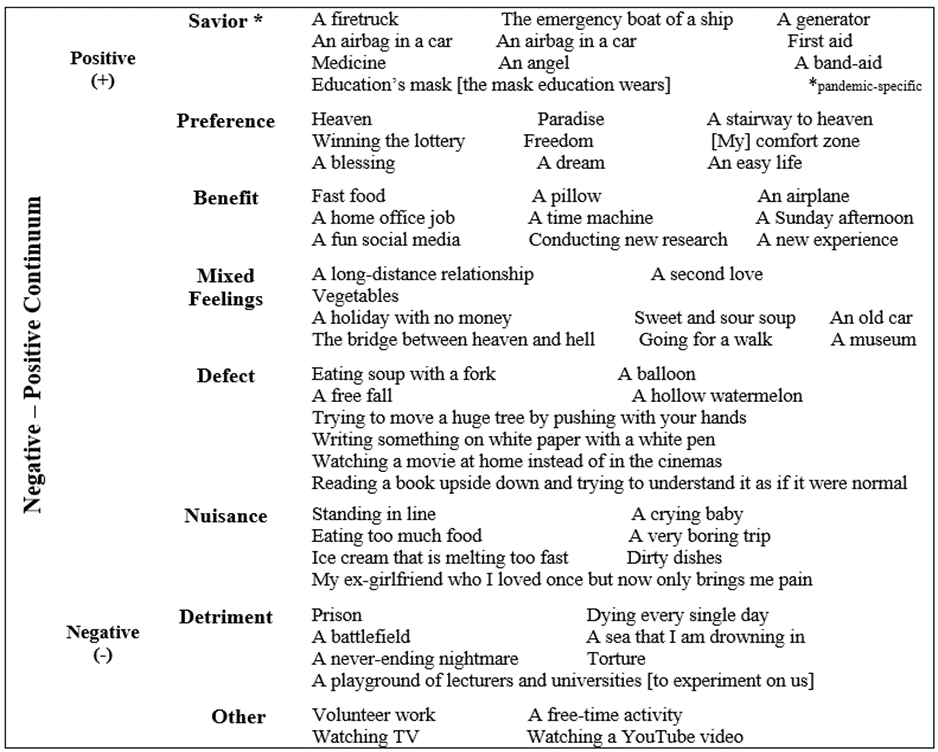

Like the teachers’ images, there were some student responses that fell into a “Mixed Feelings” or “Other” category. However, because there was a significantly higher number of student participants, the categorial system is a bit more refined and contains eight themes instead of six. Table 2 shows a selection of the most vivid student images. The categories are noticeably and understandably different because of the different roles teachers and students take in online education. This is explained more in the findings and discussion section. In addition, a “Savior” category was created for both teacher and student metaphors, which is deemed to be a pandemic-specific category due to (a) online education being forced, and (b) the likelihood that this category would not exist if the study were conducted outside of a global pandemic.

Table 2. Students’ Images

Follow-up semi-structured interviews

Both the teacher and student surveys included an item that allowed participants to voluntarily leave their email if they were willing to participate in follow-up interviews. In total, 15 teachers were interviewed – six teachers from the Preparatory English Department, six teachers from the Undergraduate English Department, and three teachers from the Second Foreign Languages Department. As for students, despite having a larger number of participants, they were more hesitant to participate in a follow-up interview, resulting in only seven interviews total – one preparatory English student, two 1st year students, and four 4th year students. Nevertheless, the detail, clarity, and insight these interviews provided was very intriguing and contributed valuable information to the overall findings in this paper. Table 3 lists the semi-structured interview questions that were asked to both teachers and students, but follow-up questions were also asked whenever the opportunity presented itself and some have been included in the table. The authors decided that the last question would be metaphorical in nature for both interviews because of their revealing nature, and pictures were included in case participants were unsure of the vocabulary used in that specific question.

Table 3. Follow-up Interview Questions for Teachers and Students

Positionality statement

In the spirit of self-reflection, the authors acknowledge how their positionality may influence the interpretations of the data collected to some extent. The lead researcher self-identifies as an education white American woman and a NS (native speaker) with nearly a decade of experience teaching English to Turkish university students, while the co-author self-identifies as an educated Turkish-British-Greek woman born and raised in Turkey with over a decade of university experience with Turkish students as a NNS (non-native speaker) teacher of English. Both researchers have positive working relationships with all of the teachers that were surveyed, and some of the students who participated in the survey and interviews were students or previous students of the lead researcher at the time data was collected. Nevertheless, the researchers collaborated to ensure objectivity to the best of their ability.

Findings and discussion

The findings came from coding and analyzing the teachers’ and students’ metaphors, running a statistical analysis of the metaphors and demographic information collected, follow-up semi-structured interviews, and comparisons of all of these.

RQ. What are the teachers’ and students’ perceptions of online education?

Teacher metaphors

- What[HK2] are teachers’ attitudes toward online education?

When creating the categories for teachers’ metaphors, some themes arose that, when looked at more closely, can serve to inform teacher development and online programs as they develop and improve even after the pandemic. These themes were also reoccurring in the follow-up interviews with teachers. The first theme that was perhaps the most obvious was that of one-way transmission, suggesting a lack of interaction with the students during lessons and issues with students participating in the chat box only, disregarding their cameras or microphones. This was evident in metaphors such as:

- Two[HK3] -way mirror (mentioned three separate times)

- Being a youtuber

- Being a radio DJ

- A bubble

- Talking to emptiness

- A radio program

Another theme that was identified was the notion of survival. Various approaches were taken to this theme with some teachers showing gratitude toward online education (being saved) while others felt more frustrated (trying to get by):

- Wilson from the movie Castaway[HK4]

- A life ring

- Weathering a storm

- A life jacket

- Jumping in at the deep end of a pool when trying to learn to swim

- A life raft with a leak

Teacher interviews were also quite revealing as they provided more detail not only to the metaphor that each teacher chose, but also to their overall experience of forced online teaching. Some teachers highlighted the positive sides of online education, such as having the chance to reflect on their teaching, developing the ability to adapt more spontaneously when lessons are not going as planned, becoming more comfortable with using technology in teaching, exploring different ways to ‘spice up’ the online classroom, as well as becoming more resourceful. However, the teacher interviews also pinpointed some of the major issues in online education, like having to change how they interact with students given the impersonal nature of the online space, lessons becoming less student-centered, and adjusting to “the difference between what we have to be and what we want to be.” A few excerpts that clearly demonstrate teachers’ issues have been transcribed:

|

Excerpts |

Issue(s) identified |

|

Teacher 1’s metaphor (Challenge): Online education is like a life raft with a leak.

“In the first place, you know, online education served its purpose, similar to the main purpose of a life raft – we did not drown, we did not sink…but at the same time, I feel like there were all these new challenges, new administrative duties, new expectations, that it felt like, you know, little leaks springing up…finally we would get to a point where we felt like ok we’ve plugged this leak, I know how to do this, I figured that out, and then another leak would spring up, like another duty…there’s a lot of little things we have to stay on top of in order for this life raft not to sink…another thing that came to mind as I was thinking more about this…I feel like we’re a lot more isolated. Before we were on the ship together, right? We could interact, we could learn from each other, build from each other’s work. In this online education environment, it feels like we’re all kind of in our individual bubbles…we do have WhatsApp groups and things, but I feel like we were a lot more active in the beginning, our life rafts were closer together and we’ve kind of drifted apart as we’ve gotten busier and deeper into our year…it’s more like a telescope. The kaleidoscope to mean represents change and creativity and lots of different patterns, like different patterns of interaction and different types of activities activities…I feel like I’ve lost some of that in the online space, you know, group work versus pair work versus whole class work, I don’t those things as much…”

|

A need for clearer administrative procedures

Feelings of being overwhelmed

Feelings of isolation

A need for more formal teacher training in online interaction patterns

|

|

Teacher 2’s metaphor (Mixed Feelings): Online education is like the end of the rainbow.

“…Everybody knows that at the end of the rainbow…there is this pot of gold…the pot of gold here is getting students to learn equally as well and have as much interest and join in with the lessons as they did when they were face-to-face. So the rainbow is now the internet lesson and the pot of gold is getting more or at least similar results out of the students, which you can normally get if you’re good at everything, I think, but I don’t think a lot of us are as ok with using the technology as we should be. I know what I want to do, but sometimes I feel…I’m not using it properly. Now that we’re on the internet, I think it ruins the teaching side, I think it makes us back into lecturers…I think I’m going backwards and I’m not going forward…because I understand the technology, it [still] frustrates me that I can’t get the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow…I feel like I’m going around in circles…” |

A need for more formal teacher training in educational technology, etc.

A lack of student interaction

A lack of teacher motivation

|

|

Teacher 3’s metaphor (Chaos): Online education is like unraveling a tangled mess of yarn.

“The English 101 units [of the coursebook] are set up with the idea that there is input and then finally there is output, and as a teacher it’s a really good way of following this linear thought, and what happens is with the online teaching, just by its very nature, it’s not linear, and so the book and the medium itself don’t really mix very well…the book is really written for students who are going to be participating, discussions and so forth…and that really doesn’t happen online, my experience as a teacher online has been teachers are unwilling to participate, especially like speaking, in class…there’s no way to necessarily find if the student has understood the idea, there’s no way to evaluate the progress that a student is making because, especially if this is based on, I mean, reading material that students don’t read…there was a great reluctance to just participate…group dynamics or social dynamics just aren’t there [in the online classroom]…it has become teacher-centered, even though breakout rooms and these [types of tools] make it more student-centered, it still just does not happen, because I don’t think the students are really familiar themselves with working in an online environment…they may not necessarily have the skills or expectations [to do this]…” |

A need for curricular adaptations (materials, activities, pacing, etc.) to be better suited for the online learning environment

A need for more formal teacher training in student motivation and classroom management, etc.

A lack of student interaction

A need for more formal learner training in developing better study habits, time management, coping mechanisms, etc. |

Table 4. Follow-up Interview Excerpts from Teachers

Student metaphors

- What are students’ attitudes toward online education?

Because students’ metaphors were greater in number and their categorization more refined, additional themes outside of the already-established metaphor categories were not as prevalent. However, they were quite striking in many cases, and there were still common issues presented by the various metaphors and their accompanying explanation that aligned with the issues identified in the teacher metaphors, such as the following:

|

Online education is like… |

Issue(s) identified |

|

volunteer work because people only participate if they really want to. |

A lack of student interaction

A need for more formal learner training |

|

a storm because I cannot keep up with the workload with so little motivation and I feel like I’m being dragged. |

A lack of student motivation

A need for curricular adaptations (materials, activities, pacing, etc.) to be better suited for the online learning environment |

|

gambling because you never know if your internet connection is good enough or not that day. |

A need for more reliable technology |

|

trying to build a building from Alaska, but construction is in Dubai because I study mechanical engineering and I need to touch and see [things]. |

A need for curricular adaptations (materials, activities, pacing, etc.) to be better suited for the online learning environment – perhaps hybrid courses for certain faculties |

|

post-drunkenness [a hangover] because it is hard to remember something afterwards. |

A need for more formal learner training in developing better study habits, time management, coping mechanisms, etc. |

|

a playground of lecturers and universities because they really like to experiment on us while expecting from us to adapt as fast as Usain Bolt. |

A need for more formal teacher training

Feelings of distrust |

|

prison because I cannot leave my room all day. |

Feelings of isolation |

Table 5. Sample Metaphors and Issues from Students

Moreover, while some interviews with students were extremely positive, with one 4th year student even mentioning it wouldn’t be possible to graduate if the semester hadn’t been online, there were also some interviews that were particularly informative in terms of students’ struggles with forced online education:

|

Excerpts |

Issue(s) identified |

|

Student 1’s metaphor (Defect): Online education is like a song :-D (smiley face in original).

“I wrote it as a joke but in the end there are a lot of things affecting our listening while online, I mean, I’m at a computer, things in the background, my phone is in my hand, messages come through…this is why sometimes our attention goes phone or other online websites and things, I’m letting the class in the background, the teacher is speaking but my attention was being on phone or YouTube or something…[face-to-face classes] getting in the

|

A need for more formal learner

A possible need for teacher training

Lack of discipline and motivation |

|

Student 2’s metaphor (Detriment): Online education is like a playground of lecturers and universities [to experiment on us].

“I was really frustrated and angry, I’m a double major student…[the teachers] changed some of the exams to be more writing…I thought I would stay home and wake up late, but then I became like an office worker but there was no 8-4 work, I have to manage that and since my motivation was disappearing I couldn’t do that, then I realized people are trying to do something without knowing the consequences, the teachers and universities encountered with this for the first time…the school just told the lecturers to make the evaluations as fair as much as you can, and they tried to do their best but without thinking about [the students]…I didn’t learn as much as I can…I even quit some courses because I didn’t learn…normally I’m an interactive student and I learn by questioning and the teachers’ experience, but in online session it’s not easy…some lecturers just reading the slides…I stopped going…I just checked the syllabus, I have to |

A need for more formal learner

A need for clearer administrative procedures regarding exams

A lack of motivation

Negative feelings associated with online learning

A need for curricular adaptations (materials, activities, pacing, etc.) to

A need for teacher training to make lessons more engaging and interactive

A concern for online cheating

|

Table 6. Follow-up Interview Excerpts from Students

Another aspect present in students’ responses was the cultural specificity of some of the images, specifically mantı without yogurt (a Turkish ravioli-style dish covered in yogurt) and the Aegean Sea. While it would be fascinating to further explore culturally-specific references, such analysis falls outside the scope of this paper.

Comparing teacher and student metaphors

- Are there any similarities or differences between the teachers’ and students’ perceptions of online education?

An initial statistical analysis of teacher metaphors and demographic information showed no significant relationship between the metaphors generated and teachers’ gender, years of experience, or previous experience teaching online. However, a frequency report shows that 39% of all responses fell into a negative metaphor category (Chaos and Challenge), 37% of the total responses were positive in nature (Opportunity, Savior), while the remaining 24% of responses belonged to the “Mixed Feelings” and “Other” categories. This suggests that teachers were evenly split between positive and negative perceptions of their experiences with forced online education at that time. In contrast, the students’ results showed a wider divide. Firstly, 51% of all student metaphors fell into a negative category (Detriment, Defect, or Nuisance), 31% generated a more positive metaphor (Benefit, Preference, or Savior), while the remaining 18% of responses belonged to the “Mixed Feelings” or “Other” categories. Interestingly, the “Mixed Feelings” category of both teachers and students was exactly 14%, though there is no explanation for this. Overall, these statistics show that students in general had a more difficult experience than teachers for a variety of different reasons. Secondly, while there was no significant relationship between students’ metaphors and gender or year in school, there was a significant value of 0.094 for easy access, meaning that whether or not students could easily access their online courses (having reliable internet, a working computer, etc.) affected the type of metaphor they generated, specifically one that fell into one of the three negative categories (Detriment, Defect, and Nuisance). In numerical terms, 70% of students who could not easily access their courses chose a negative metaphor. The situation was especially difficult for students from lower-income backgrounds and whose families lived in more remote areas, but in an attempt to ‘even the playing field’ for students, the school decided to implement a pass/fail option for students as an alternative to the grade they received for both the Spring and Fall 2020 semesters.

When comparing the overall responses of teachers and students, there are some clear similarities and differences. Both highlighted logistical advantages and disadvantages, such as being able to stay on track for graduation or continue working, saving time because of not commuting to the school, having more or less time to study or develop new activities to try in class, and even back pain from having to sit in front of the computer for long periods of time. Yet, in perhaps oversimplistic terms, it seems as if teachers responded from a more reflexive standpoint of how they were figuring out and using online tools to conduct online lessons (the Blackboard© LMS, various educational technology, etc.), whereas the students seemingly responded from a more evaluative standpoint of the mode of education itself with a type of ‘it works, it does not work’ perspective, generally speaking.

-

- How does the teachers’ attitude toward online education impact their teaching?

In a sense, nothing has changed for the teachers – they still call upon the same subject knowledge, teaching expertise, and in many cases the same materials as before the pandemic when ‘giving’ their lessons. However, though many see forced online education as an opportunity to develop a new teaching skillset, others have felt outright undermined by the situation: they are unsure how to gauge student understanding and progress in synchronous lessons; they are unable to interact with students in ways that are familiar to them; they have difficulty establishing the type of rapport with students that suits their teaching style; they feel their lessons have lost some creative and interactive momentum; and, though they seemingly have all the pieces, they are unsure of how to put together the puzzle of effective online lessons in their particular context.

- How does the students’ attitude toward online education impact their learning?

Students, on the other hand, experienced the situation differently, as expected. While some students were grateful for the freedom created by forced online education, others were intensely unhappy with their experiences because the way in which they ‘receive’ it has drastically changed: they struggle with the lack of (informal) social interaction with classmates, the hands-off approach to lessons that they feel should be more hands-on, the seeming lack of trust both in and from some teachers, and especially the newfound responsibility that has been placed on them to take a more active role in their learning considering the teacher is seen as being less present in the online space.

Suggestions

Considering everything that has been discussed so far, as demonstrated by the sample metaphors, statistical analysis, and follow-up interviews, it is clear that actions need to be taken in order for online programs and the teachers and students involved in them to be successful. This section aims to clarify what some of those actions look like.

In regard to teacher development, McGrath (2006) outlines a wonderful 11-step procedure involving metaphor analysis for a teacher development activity in groups. It consists of teachers sitting together, coming up with their own metaphors to a particular prompt, writing them on the board, discussing them, categorizing them, and making comparisons between groups. This is an oversimplified summary of the activity, of course, and the researchers encourage readers to refer to the full activity in McGrath’s work. For this article, the authors have adapted steps 2, 9, and 10 of McGrath’s activity, which can be done by teachers individually, to match the topic of this article: online education. We have described these procedures in Appendix B, and we believe it would be an extremely insight activity for teachers to complete. As McGrath (2006) mentions, “…if this happens to be a teacher’s first attempt to understand what their learners feel, to listen to their learners’ unique voices, this may trigger a new phase in self-development,” (p.179) and the authors are in full agreement.

There is also a clear need for proper training in an online program. The researchers believe teacher training should include instruction on educational technology, student motivation, classroom management, and online interaction patterns. Likewise, students also need proper training in learner autonomy, especially time management, coping mechanisms for boredom and stress, and developing more efficient study habits, as the demands of online lessons (particularly those with asynchronous components) are quite different from those of face-to-face classes. Secondly, teacher and student well-being should be a larger part of online program preparation. While it is unfair to blame online education for teachers and students feeling stressed, isolated, or overwhelmed during a pandemic that emphasizes social distancing and lockdowns, the lack of face-to-face social interaction that comes along with online education is inevitable, and coping mechanisms for both teachers and students should be included in the aforementioned training as well as encouraged throughout the duration of online programs, which could take the form of periodic workshops or even activities integrated into the curriculum. The curriculum itself is the third focus for action, as online education requires materials, activities, and assignments that lend themselves to the online space. This could include a more strategic use of educational technology, rethinking the pacing of syllabi, incentives for using microphones or cameras (such as making them mandatory to some extent), as well as possible hybrid courses for certain faculties, such as engineering or medical faculties. Though this last suggestion is difficult to achieve in the midst of a pandemic, future online programs could certainly consider it. Lastly, educational institutions should have clear planning and organization behind their programs, that is, having clear and well-researched administrative and pedagogical systems in place that outline clear procedures and account for any issues that may arise, and thus rolling out the program only when it is ready, not when it is convenient or lucrative for the school.

Limitations

As with any type of qualitative method, there were a variety of limitations in this study. As a reminder, Ortony (1975) notes that metaphors rely heavily on the comprehender’s knowledge of the topic and his/her ability to transfer the most reasonable and appropriate ‘distinctive characteristics’ from the known to the lesser known – or in this case, the researchers’ knowledge of the topics presented in the teacher and student metaphors and their ability to transfer the most reasonable and appropriate ‘distinctive characteristics’ from the topic of the metaphors to online education. With this in mind, it is possible that for some metaphors, the researchers did not construct an appropriate set of ‘distinctive characteristics’ and therefore failed to grasp the metaphor or even attributed inappropriate or unintended characteristics to the topic and thus misunderstood. Indeed, “there are cases where a single sentence will mean different things to different people,” (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, p. 12), and this is important to remember because “metaphors inherently encompass biases or selective knowledge that can be a way of “not seeing” (Morgan, 1997), not to mention the risk of assuming people “metaphorize” in the same way (Case et al., 2017),” (Austin and Ozkurkudis, 2021, p. 15). However, given the thorough analysis that was conducted from three different angles (categorization, statistical analysis, follow-up interviews), this is unlikely. Also, despite the promise of total anonymity, the researchers have some suspicion that a few teachers were not entirely truthful during the follow-up interviews, as they may have been hesitant to be critical of their school or how it has handled the switch to online education, particularly the more experienced teachers who have held administrative positions in the past and part-time instructors hoping their contracts will be renewed. “Inherent in any such attempt to make the implicit explicit, however, is the tendency of those being questioned to say what they think they think (or, worse, what they think they ought to think),” (Thornbury, 1991, p. 198). Despite these limitations, rather than using these arguments to push for the creation of an even more ‘objective’ set of methodologies, the researchers dare to argue the opposite – Packard (2008) suggests that since there is no real way to eliminate subjectivity completely, researchers should focus on the value of reflexive approaches and take measures to identify and explain any areas that may include biases whenever possible. This is exactly what the researchers have attempted to do.

Conclusion

Metaphors, as figurative language, are closer to emotional reality and perceptual experience than more literal language could ever be in many instances (Ortony, 1975, p. 50-51). It might seem like the same results can be determined from simply asking teachers and students to list the issues and benefits they have experienced with online education, but the images rendered by metaphors tell us so much more. In fact, Lakoff and Johnson (1980) have gone so far as to consider the ability to comprehend experience through metaphor as another one of our senses, like seeing or hearing or touching, since in many cases metaphors provide the only way to experience and perceive much of the world (p. 239). Thus, it is the hope of the researchers that this paper has established, along with decades of research, that metaphors are more than just decorations for language to be used in poetry and storytelling. Rather, “the human conceptual system is metaphorically structured and defined,” and thus the thought processes of humans are largely metaphorical in nature (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, p. 6). In regards to method of metaphor analysis, although Tracy (2019: 252) notes there have been studies showing the drawbacks of a forced metaphor approach, namely that some people are unprepared to adequately articulate the meaning of a metaphor while others may struggle to come up with a metaphor and just give a cliché or obvious response, it is still undeniable that metaphor analysis is a powerful tool that clearly shows “…there is value in verbalizing attitudes and that metaphoric language is particularly revealing of the subconscious beliefs and attitudes that underlie consciously held opinions,” (McGrath, 2006, p. 172). This is particularly the case in this study, which argues that metaphor analysis can be a unique tool to illuminate opportunities for teacher development and improvements for online programs. Sometimes just being made aware can spark a change for the better.

References

Austin, H. and Özkurkudis, M.J. (2021). Teachers' Responses to the Prompt 'Online Education is like...': A metaphor analysis. TESOL Turkey Professional ELT Magazine Online, 4 (7): 13-16.

Case, Peter, Gaggiotti, Hugo, Gosling, Jonathan, and Caicedo, Mikael Holmgren (2017) Of tropes, totems and taboos: reflections on Morgan's images from a cross-cultural perspective. In: Örtenblad, Anders, Trehan, Kiran, and Putnam, Linda L., (eds.) Exploring Morgan's Metaphors: theory, research, and practice in organizational studies. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, (pp. 226-245).

Lakoff, G. and M. Johnson. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lawley, J., and Tompkins, P. (2014). Metaphors in Mind: Transformation through symbolic modelling. The Developing Company Press.

McGrath, I. (2006). Teachers’ and learners’ images for coursebooks. ELT Journal, 60 (2): 171-180.

Morgan, G. (2006). Images of Organization (3rd ed.). London, England: SAGE.

Moser, K. S. (2000). Metaphor analysis in psychology-method, theory, and fields of application. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1 (2): Art.21.

Ortony, A. (1975). Why metaphors are necessary and not just nice. Educational Theory, 25 (1): 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.1975.tb00666.x

Packard, J. (2008) ‘I'm gonna show you what it's really like out here’: the power and limitation of participatory visual methods, Visual Studies, 23(1): 63-77

Redden, S. M. (2017). Metaphor Analysis. In Matthes, C. S. Davis and R. F. Potter (eds.) The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, Wiley-Blackwell.

Thornbury, S. (1991). ‘Metaphors we work by: EFL and its metaphors’. ELT Journal 45 (3): 193–200.

Tracy, Sarah J. (2019). Qualitative research methods: collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact (2nd Ed). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Zheng, H., & Song, W. (2010). Metaphor Analysis in the Educational Discourse: A Critical Review. Us-China Foreign Language, 8 (9): 42-49.

Appendix A

|

Descriptors of Student Response Categorizations |

|

|

Detriment |

Suffering, punishment, or injustice; a sense of being a victim or feeling trapped

|

|

Nuisance |

Annoyance, inconvenience, or difficulty; a sense of frustration, tediousness, or demoralization |

|

Defect |

Inadequacy, unreliability, or unpredictability; a sense of impracticality, inefficiency, or ineffectiveness |

|

Mixed Feelings |

Duplicity, mediocrity or awareness; a sense of tolerance or rationality |

|

Benefit |

An advantage or convenience; a sense of ease or usefulness |

|

Preference |

A more favorable alternative; a sense of relief, freedom, or enthusiasm |

|

Savior * |

Allowed education to continue; a sense of gratefulness or feeling lucky *pandemic-specific |

|

Other |

Images with explanations that did not clearly lend themselves to the positive/ negative continuum |

Appendix B

Individual Teacher Development Activity (adapted from McGrath (2006, p. 180)

- Teachers can come up with their own metaphors regarding the topic of online education by complete a metaphor prompt similar to the one in this study (“Online education is like…”). Then they should come up with a ‘because’ sentence and take time to consider why they might feel this way or what underlying assumptions they might hold on this topic.

- As a follow-up task, the teachers can then have their students complete the same metaphor prompt with a brief ‘because’ sentence on a slip of paper (with the ‘because’ sentence on the back), though this assumes their students have a proficiency level that is suitable enough to complete the task.

- The teacher collects the slips of paper, categorizes them, and reflects on them to determine (a) any differences between the image they themselves generated and those of their students, (b) whether the students’ images apply more to the specific online platform being used, the way online education is utilized (the type of assignments given, the lessons, the teachers, etc.), or its effect on them, and (c) whether they can see any implications for how online education can be used more effectively.

Please check the Pilgrims f2f courses at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pilgrims online courses at Pilgrims website.

Top 5 Tips For Teaching English Online

Simon Dunton, UKTeacher and Student Images for Forced Online Education

Heather M. Austin, Japan;Mary Jane M. Ozkurkudis, TurkeyEFL Teachers Experience in Conducting Effective Learning Activity During COVID-19 Outbreak

Anda Roofi’ Kusumaningrum, Indonesia;Andhika Wahyu Rustamaji, Indonesia;Eric Dheva Tachta Armada, Indonesia;Rahmadilla Kurniasari, Indonesia